SOCIAL CHANGEMAKERS BLOG ISSUE NO.7: GOPAL SHIVAKOTI, DOCUMENTARY MAKER: Documentary making requires you to follow your passion and start

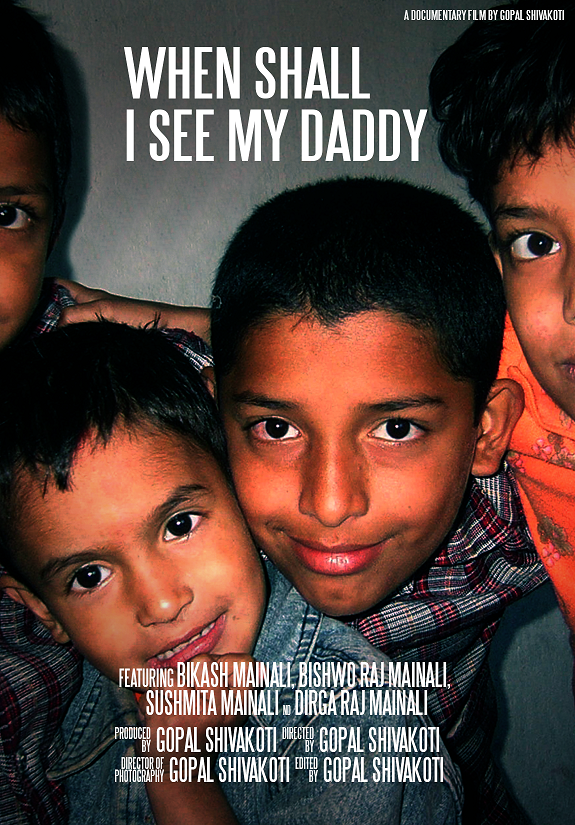

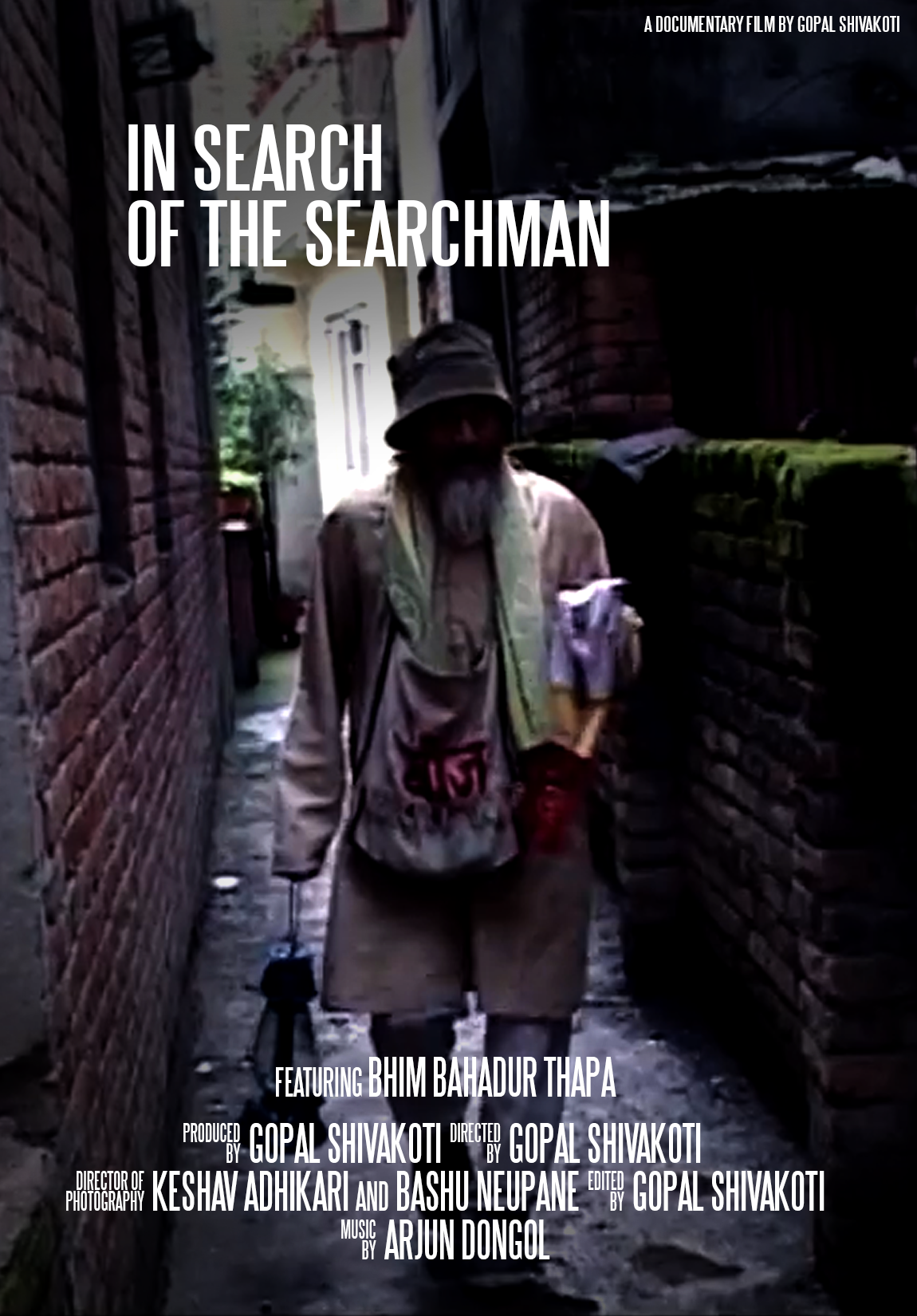

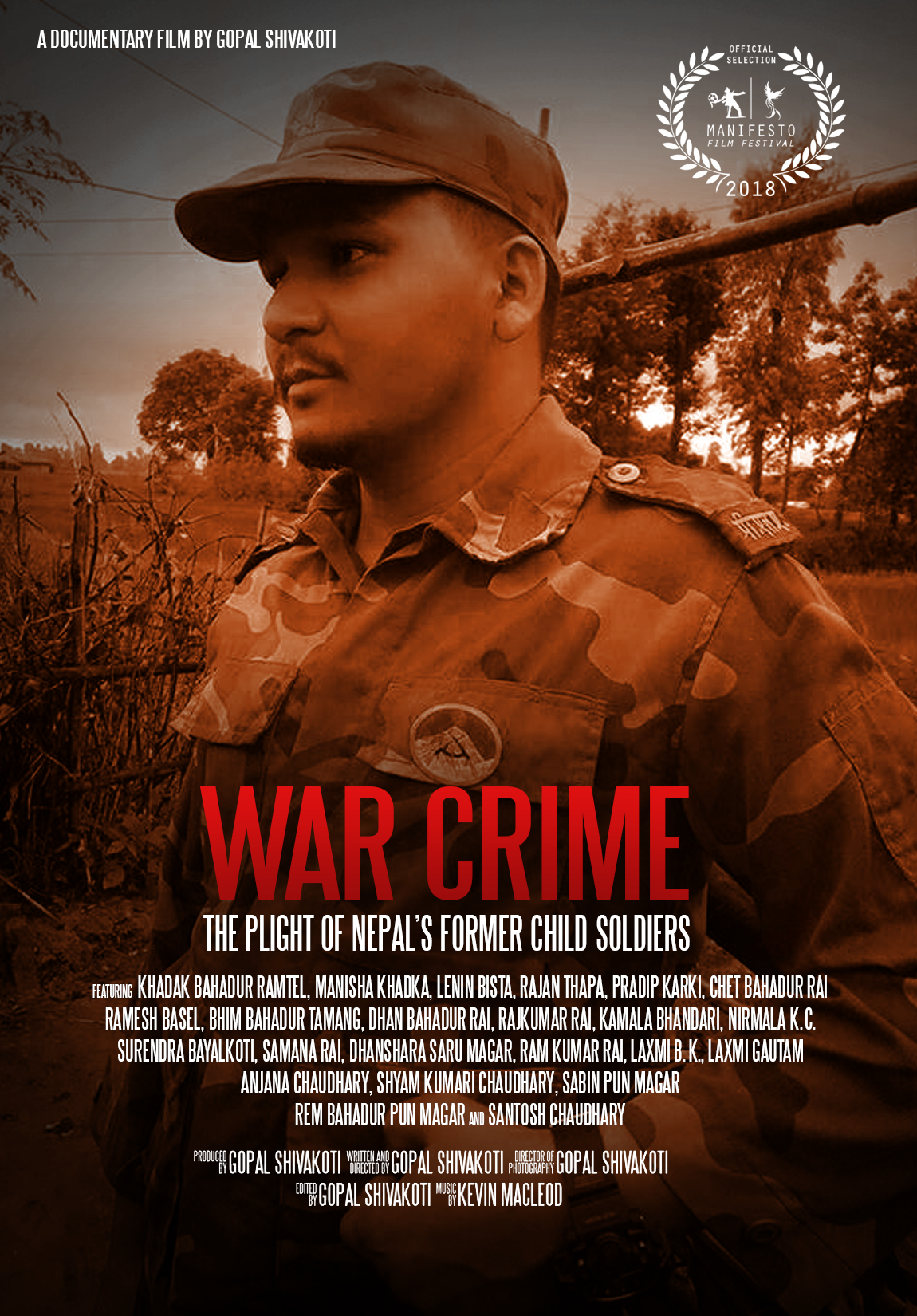

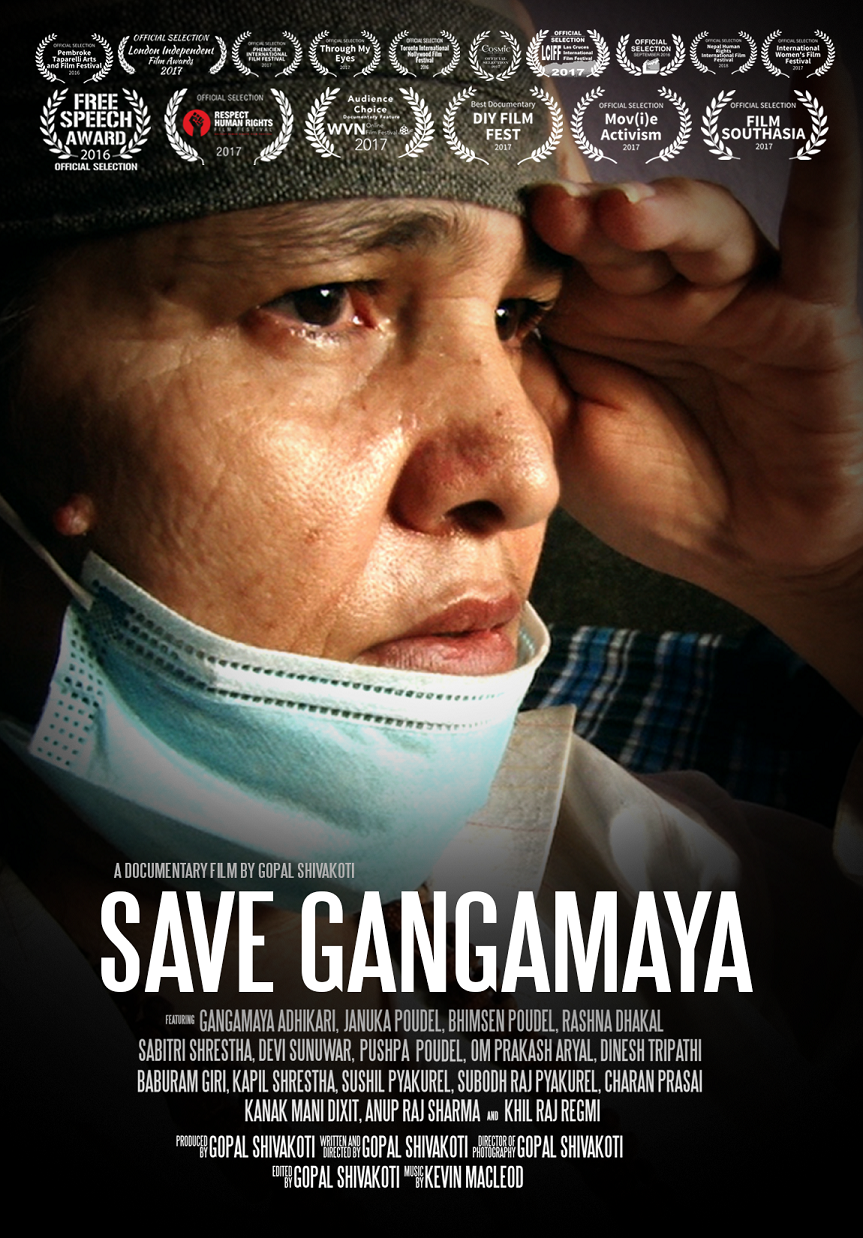

Giles Duley says ‘Documentary has always come with great responsibility. Not just to tell the story honestly and with empathy, but also to make sure the right people hear it.’ Quite similar to Duley’s definition, Gopal Shivakoti, an independent documentary filmmaker of Nepal uses his documentaries as a tool to tell the story of the persons, who raise their voice and bring an impact to society. Shivakoti has been working in this field since 2004. Since then he has successfully worked on many documentaries, notably; ‘Save Gangamaya’, ‘War Crime’, ‘We are with Dr. KC’, ‘Pinky Gurung’, ‘In Search of the Searchman’, ‘When Shall I See My Daddy” etc. The Catalyst met with him to talk about his documentaries and how documentary filmmaking has helped to influence people and create an impact.

What motivated you in documentary filmmaking? Where do you see yourself standing now?

I have been interested in films since school. Around 2003, I joined the National Studio of Film Training (NSOFT) where I learned film directing. Then I moved on to learning editing and animation then I gradually shifted towards documentary filmmaking.

It's been 12 years since the start of my journey and I am still learning. The perspective to look at my own work has changed. In my early phase, I was a little fearful about my documentaries, whether they would be accepted or not, or if people will like ithem or not but today this fear has disappeared. Through my documentaries, I am able to reach a great number of people.

Can you share your experience of the first documentary shoot?

My first documentary is ‘In Search of the Searchman’. On my way, while walking, I used to see ‘Khoja/Search’ written on walls at various places. In the beginning, I thought it might be the campaign of some political party. But one day, I saw an old man writing it on the wall. That day I ignored him, but after few days I realized his story would be interesting. I went on to search for him for months, but couldn’t find him. I asked many pedestrians about this man, which got me to the characters of my documentary. I took my camera and recorded everything. I was not sure whether he would agree or not. What I thought was, I can at least shoot while searching. Fortunately, I found him, all my curiosity got answered which resulted in this documentary.

What is the main work or purpose of the documentary?

For me, documentary does two to three things. Firstly, it is that it documents and conveys the information and message to an audience. Secondly, the viewer who watches the documentary can learn new things and update his/her perspective and awareness towards that issue. Lastly, if anyone has documented or visualized a situation or person, this can easily be accessed after 50 years.

Documentary makes any issue eternal and serve as a vital tool to both educate and inspire. If done well, documentaries have the power to transform, move, and change the world.

There are many ways to document an issue, like a sketch or biography, so what is the difference in capturing it with a camera?

All these mediums’ purpose is the same. The major difference with writing, art or photography is that all these things can be gathered from a documentary. The things to be said by an author or a writer also comes in the documentary. Even the story to be conveyed by a painter from the sketch comes in it. The camera can be considered as a more influential recording tool. This newspaper was brought in the morning (showing newspaper), but I have not read it yet. Had it been in the form of a visualization, I would have probably watched it. The camera makes the issue more alive in a way that directly connects to the audience.

How can a documentary be one of the tools for bringing social change?

Over the past few years, drug policy reform in Brazil, immigration rights in the US, non-violent resistance in Palestine and Dalit movement in India have all been impacted by powerful documentary films.

What are the reasons behind the making of ‘Save Gangamaya’? In the context of the growing indifference towards her demands, how do you see your work pressurize the government and the public to wake up and address human right issues?

The main reason for making ‘Save Gangamaya’ was because of I find the story of her and her husband very painful and critical. It was during the ‘Occupy Baluwatar Campaign’ when I first saw and heard them speak. The campaign was related to women’s issues. People used to gather in front of Baluwatar (PM’s residence) and speak. The floor used to be given to women leaders to put forward their views. There was an old man who used to stay beside the mike every time. He looked as if he was trying to say something. One day, he was given a chance to speak up. Then the story of Nanda Prasad Adhikari came up. He came from Gorkha to Kathmandu with his wife Gangamaya for the justice of their son. Their teenager son was killed during the Maoist Insurgency period. He told the entire story of how they came and how they were struggling for seeking their rights demanding the punishment to perpetrators. The couple was sent to different places, from Singha Durbar to mental hospital and to Bir hospital where they were given a forced treatment due to their hunger strike. After listening to his story, I thought of making this documentary about them. I wanted to cover both of them, but they were under a prominent security of the police at the hospital and hence it was not possible for me to get chance. In the course of their hunger strike, Nanda Prasad took his last breath leaving Gangamaya all alone in their fight. But she continued with the same dedication and I was able to talk with her.

Honestly speaking, this documentary did not help Gangamaya. There was no immediate impact either. Still, her condition is the same today. Gangamaya herself told that it was not possible to go against the political parties and the government. But she thanked me for creating a record of her struggle. She is hopeful that if not this government, this video will touch the hearts of millions of people who will be added to the population. And from my part, at least I showed the future generation that people were not indifferent towards her rights.

You were aware of the risks associated with sensitive issues when making documentaries. You received threats while working on ‘Save Gangamaya’ , but still you chose an even more sensitive issue by making ‘War Crime’. What excited you about this issue?

Human rights, corrupt governments, poverty, education, war crimes, domestic abuse… these difficult issues need the spotlight. And these are not easy issues to tackle as a filmmaker. It takes guts and courage to jump in and try to make sense of it all and create a story because we believe sometimes life can be ugly.

And as long as ugliness is hidden from view, perpetrators can continue unchallenged. But if suddenly a bright light shines down on these heinous acts, the good people of this world can see it, examine it and hopefully do something to fix it. Hence, we take risks. Speaking for those who can’t speak for themselves; giving a voice to the most vulnerable in our society including children, the elderly, animals, the environment, the poor and disabled. The documentary ‘War Crime’ is an example of this. War Crime exposes the story that during the 10-year conflict (1996-2006) in Nepal, Maoists recruited children as spies, cooks, porters and even frontline guerrillas. 10 years after the conflict ended, the Nepal government and the party they were ready to die for have forgotten them. The former Maoist child soldiers are now in their 20s fighting for survival and against social stigma.

You have made another documentary too named ‘Pinky Gurung’. Could you tell us something about this documentary?

My documentary "Pinky Gurung" is centered on the life struggle of "Pinky Gurung" and her journey from boy to trans genderwoman social-worker and leader in Nepal.

We know members of Nepal’s LGBTI community were once openly derided as “social pollutants,” but now they enjoy social and political rights including legal recognition of a third gender that has put the country leagues ahead of much of the rest of the world. The past decade has proved critical in that evolution, as LGBTI activists won significant victories in Nepal’s courts. Gurung is of the view that there is a need for representation of transgenders in the new parliament to raise the voices of gender and sexual minority.

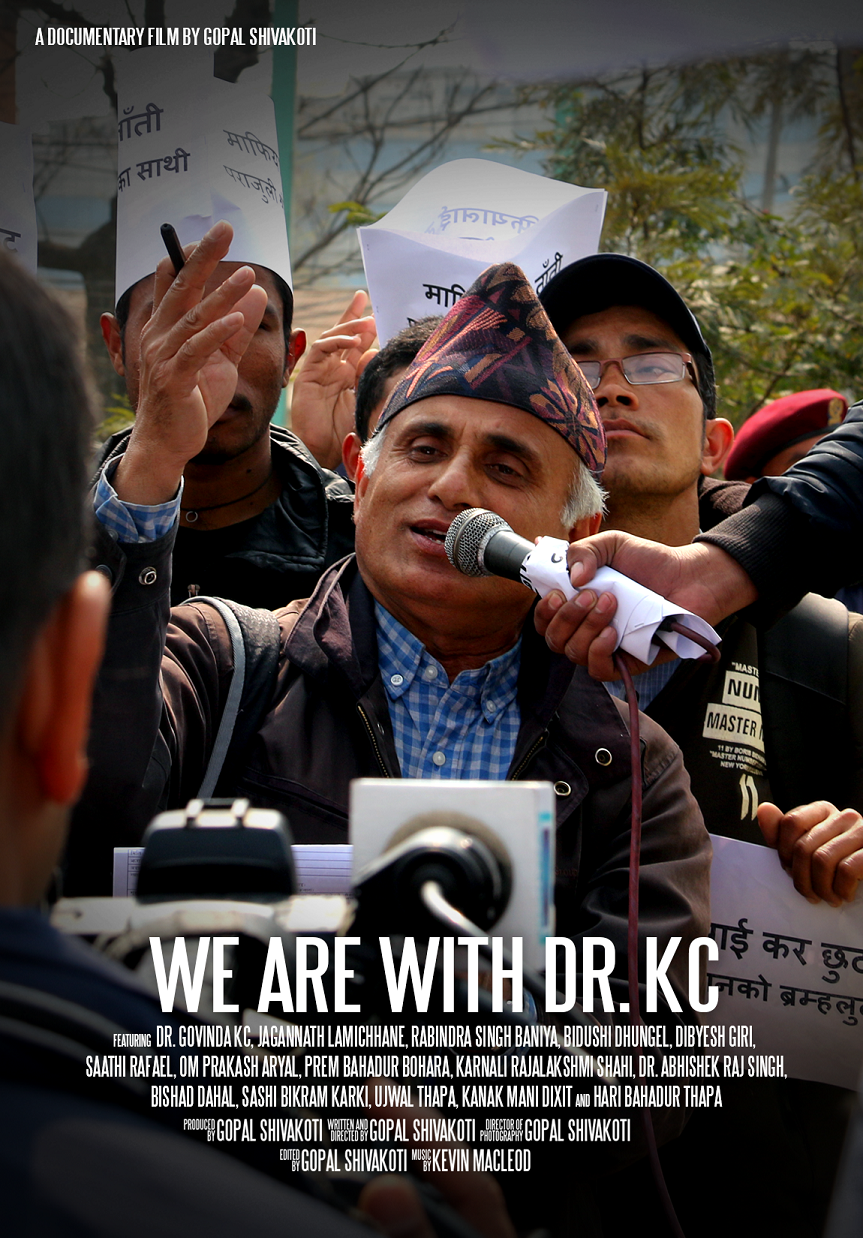

Now I am working on my next project ‘We are with Dr. KC’. It would be a feature-length documentary film about Prof. Dr. Govinda KC and his non-violent campaign for medical sector reform and good governance. We all know his ongoing advocacy over several years has included several lengthy personal hunger strikes, which have successfully pressurized the authorities to make some changes.

So, this documentary is an expression of gratitude to Dr. Govinda KC for being a singular voice of reason and moral authority in a place where the moral compass of political leaders swings like a pendulum.

All of your documentaries are focused on human right issues. Why?

Human rights is the kind of issue that the people do not normally openly speak about. In Nepal, to talk about the human rights issues, one has to either have their own INGO or someone should be ready to take the risk of speaking up. And it is difficult for many to take the risk. For instance, after the documentary of Gangamaya, it has been difficult for me to move around freely because the people from whom I took the interview keep asking why I made the documentary and why I didn't do it in their favor. So, this sort of work is a little daring one and I do it because I feel someone must speak up about these issues.

What impact can documentary films have on society?

Talking about today’s scenario, documentary has helped to bring about certain changes in society. There is a documentary from Egypt, ‘The Square’, which was successful to bring the revolution which later changed the government. We can learn the real situation of other countries through them. The documentary recorded all the violence they are facing and spread this message. It inspired the people to start capturing all the moments that they suffer and publishing those on the web. They also ran a campaign with the help of such documentation. This way it can help to bring about change in society and in the perspective of people. The words of people may change in the future, but once they are recorded they are obliged to stay truthful. A documentary also provides information that can be useful when conducting research or can even provide a basis for someone interested to make a movie out of it.

How difficult has it been to reach to the youths? How do they respond to the issues raised through your documentaries?

Documentary films are different from tmainstream films, as they have a responsibility to carry a reality. From it, one can get closer to the truth than from a fictional or entertainment film. People also get to know the present context more directly from documentaries and the message circulates faster among youth. Likewise, one can understand the situation and be aware of what can be done in such situations and how to avoid such situations in the near future. In Nepal, reaching to youth is quite difficult, because most of them are indifferent towards serious issues. But those who are watching, they are quality youths and they have the courage to do something for the society.

Your most recent works have been screened at various film festivals. Filmmakers are often blamed for making films targeting international festivals only. What do you think about this?

It is necessary to make a documentary with a passion as well as to highlight social issues. People make one documentary and to make others I think Film Festivals are a motivation for us. We make so many documentaries investing so much time and hard work, but often these do not fit in the theme of any film festivals. It is essential to prepare a documentary focusing on these festivals by matching one's passion plus the theme. If the documentary is prepared without focusing on the film festivals, it is hard for them to get recognized and they might not be accepted by the distributors or any channels. It is not even screened on any schools or colleges. And even while approaching for screening, people watch the trailer first and ask how many festivals has it been recognized, has it won or selected and all. Adding to this, once it is screened in the film festivals, the maker gets the screening fee and a motivation to make another one.

Dorothea Lange says, ‘A documentary photograph is not a factual photograph’ what do you have to say about this statement?

Documentary film is also “edited” form of film. Yes, the reality is being filmed, but how the director chooses to present it, how the narrative is crafted, shapes a new reality. So, the fine balance then becomes how to represent the “real reality” truthfully, while also creating an engaging narrative with a story arc, that audiences can engage with.

The issue can be one, but the angle of story narration can be little different. While doing my latest work, I approached to Dr. Govinda K.C to make a documentary on him. But he refused. Still, I did it by narrating the story from his supporters perspective. As it is a subjective matter, the two version vary but both are real things shown from the maker’s vision. As the story passes through editing, one can make the documentary focusing on all the positive aspects or by focusing on all the negative aspects only. The documentary, while being real, is edited.

Lastly, what message you would like to give to upcoming documentary makers?

Lastly, the message that I would like to deliver to the youths who are interested in documentary film making is that if you really want to make a documentary then go ahead. Don’t wander after worrying about how to make it or where to learn from or the resources required for it, but begin to make it and in this process, you will learn. Just have the passion and commence with the making of the documentary!