Citizenship in Nepal

One year after the adoption of the new Constitution, women’s right to citizenship has been further curtailed with the recent passing by cabinet of the draft Act amending the Citizenship Act 2006. Following, the adoption of the Constitution in September last year, the Government has been working on amending the Citizenship Act, which sets out more detailed provisions for attaining citizenship to ensure conformity with the Constitution. According to the Constitution, any person whose father and mother are citizens of Nepal is entitled to Nepali citizenship by descent. However, Clause 8 of the draft Citizenship Act has made it mandatory for a woman born to Nepali parents, but married to a foreigner to produce official documents from the authority of her husband’s side as a proof of not having acquired any citizenship. The draft has been tabled at the House of Representatives and is now awaiting approval.

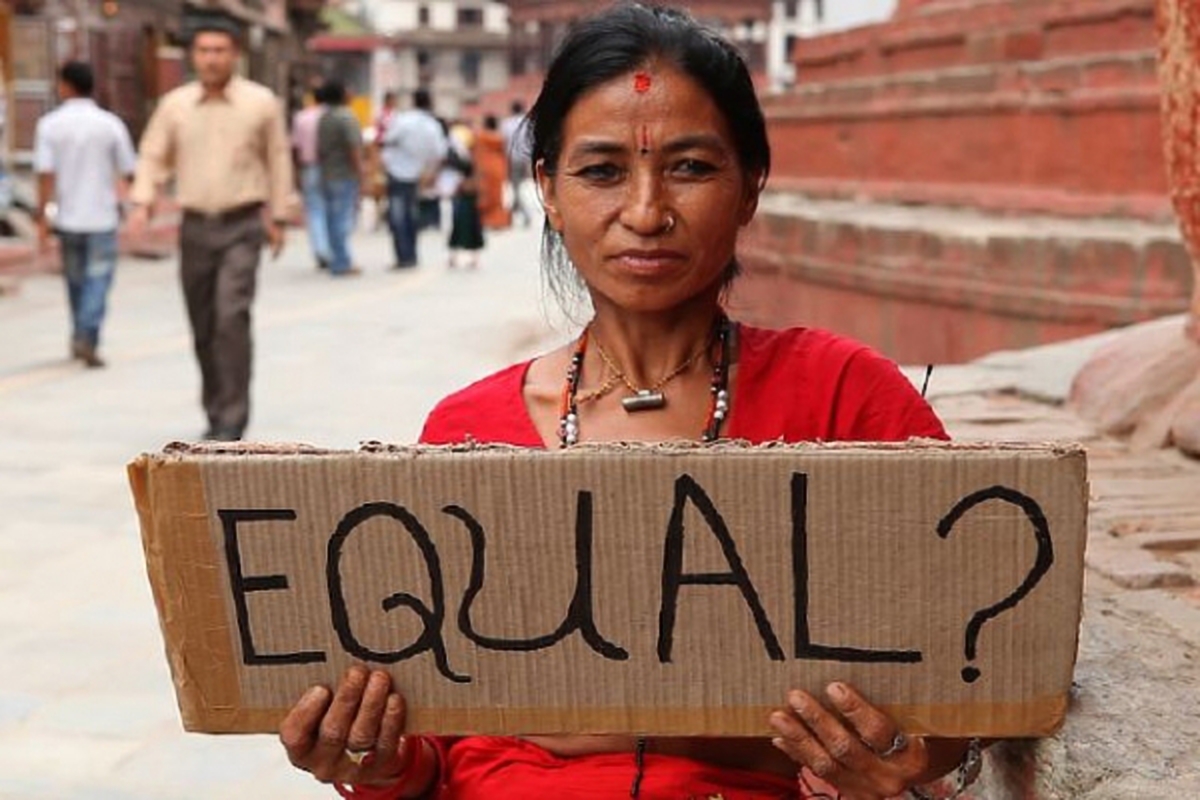

The restriction on passing citizenship adds fuel to the already heated debate about the Constitutional citizenship provisions that make women second class citizens. Much of the debate leading up to the adoption of the Constitution as well as following its passing has centered between the “or” and “and dichotomy. Whereas the current Interim Constitution of Nepal (2007) and the Citizenship Act of 2006, all provide for citizenship if a child is born to a Nepali mother or a Nepali father, the new Constitution, while containing a similar provision in article 11 (2), in section while (3) overrides this by requiring that both the father and mother need to be citizens. This provision combined with subsequent provisions that limit women’s right to pass on citizenship in particular pose challenges for single mothers in case the father has not acknowledged the child as well as for children with a foreign father.

The Constitution discriminates against children born abroad to single mothers. Thus, it only allows children born in Nepal to a Nepali mother whose father is unknown to transfer citizenship. According to article 11.6, only a person with domicile in Nepal, who was born to a Nepali mother, who has citizenship and whose father is not known shall be conferred the Nepali citizenship by descent. If his/her father is a foreigner, however, the citizenship of the child will be converted to naturalized citizenship. By requiring that the child is born in Nepal, the Constitution inhibits single mothers who have been trafficked or who have migrated abroad to transfer citizenship to their children in case they are born outside Nepal. In addition, the Constitution places the onus of proof on the single mother to proof that her husband is not foreigner as she is not allowed to confer citizenship independently. And if she cannot prove this, or if the father denies their relationship, her child may not be able to obtain Nepali citizenship.

Furthermore, the Constitution makes a distinction between the type of citizenship that children born to a Nepali mother but a foreign father can acquire. Thus, according to article 11.7, a child born to Nepali woman citizen married to a foreign citizen, may acquire naturalized citizenship of Nepal if the child is having the permanent domicile in Nepal and has not acquired citizenship of the foreign country; whereas children of Nepali men married to a foreign citizen are entitled to citizenship by descent. Article 11.7 goes on to state that if the child’s father and mother both are the citizen of Nepal at the time of acquisition of the citizenship, the child if born in Nepal, may acquire citizenship by descent. This is based on an assumption that a foreign spouse of Nepali woman may have acquired naturalised Nepali citizenship by then. Yet, article 11.6 only grants foreign women married to a Nepali citizen, naturalized citizenship, so defacto foreign husbands are excluded. Thus, children born to a Nepali mother with a foreign husband cannot obtain citizenship by descent.

Te discriminatory provisions are a reflection of Nepal’s patriarchal society and based on false notions of national security. Deep rooted patriarchal value systems dictate that women are seen as inferior to men, who dominate most parts of society including government. As a result, citizenship and nationality have traditionally been transferred from the father only. While the Interim-Constitution allowed either parent to transfer citizenship, in practice many requests filed by single mothers for citizenship ID cards have been refused by district authorities which are primarily made up of men. In the debate about the ‘or’ and ‘and’ clause, arguments of national security, national sovereignty and nationalism have also been advanced. In particular, fear of land falling into foreign ownership and foreign domination if Nepali women married to foreigners are able to transfer citizenship to their children have been used as pretense to justify the restrictive provisions.

The Constitutional provisions make an entire generation of young people stateless. Already, more than 4 million people are estimated to be stateless in Nepal. The Constitutional provisions will increase the number of statelessness youth without access to the rights of education, health care, among others. Without an ID card one cannot vote, to get a driver's license, open a bank account, or study at a university. They also do not have access to formal employment and cannot register their business etc. Furthermore, stateless youth are likely to experience reduced marriage prospects especially girls as societal values will attach a lower status to them because of the fact that they lack citizenship.

Apart from not being able to claim their rights, the Constitutional provisions put young people in particular young women at risk of exploitation. Without any education, job and marriage prospects, one of the few alternatives that remain for stateless youth in poor remote areas is to go abroad for work or to find a marriage partners. In the absence of any legal documents, they will be forced to resort to illegal channels and in many cases will opt to work abroad in India because of its open border with Nepal. This increases their vulnerability to economic exploitation at the hands of scrupulous recruitment agencies and middle men. It also increases the risk of trafficking and sexual exploitation especially of Nepali girls, who often are often lured with false promises of marriage and end up in brothels of Mumbai, Siliguri, Delhi Bangalore or Kolkata.

Nepal’s Constitutional provisions are in violation of several of its international human rights obligations. While Nepal has not ratified the Convention Against Statelessness and the Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, the right to nationality is provided under the Convention Against Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which both have been ratified by Nepal. The Constitutional provisions are also a violation of the right of women to freely choose their spouse as provided for in CEDAW.

In order to ensure the equal rights of Nepali women and children to citizenship, action needs to be taken on various fronts. While Constitutional provisions are difficult to change, the Supreme Court in Nepal has the ability to set a precedent when it comes to interpretation of Constitutional provisions. In a landmark ruling in 2011, the Constitutional Court ordered to a girl, whose father was never identified, was a Nepali citizen on the basis of her mother’s citizenship. It seems that it is time for the Supreme Court to issue a new ruling based on the new Constitution. At the same time, if the Government is not willing to change the Constitution, at least ensure that stateless persons are able to enjoy basic rights.. At the same time, more investment should be made in awareness programs for young people, so that they at least the are sensitized about gender equity, identity, social inclusion and citizenship in order for social norms and values to change over time. In this regard, the current generation of young Nepali have an important role to play in taking more of an active role in the debate around citizenship and standing up for their fellow peers who by virtue of not having citizenship are not able to exercise their democratic rights.